A frequent criticism of the Allowance for Credit Losses is the disconnect created between the recognition of income and expense. Financial institutions are forced to record life of loan credit loss expense at origination, whereas income is recorded as it is earned.

This deviates from the traditional ‘matching principle’ that is generally accepted. The criticism is a fair one. However, to think this should impact a financial institutions’ lending or underwriting strategies is short sighted and ultimately impactful to your ability to serve your community.

I think it’s important to illustrate this.

All Else Equal, Expense will not Change

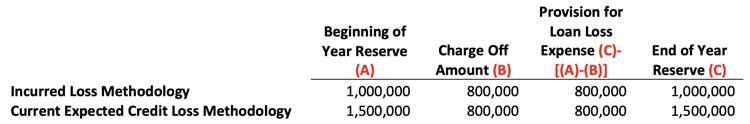

Provision for loan loss (PLL) expense is the expense recorded in order to increase the allowance for credit losses. Generally, your allowance is decreased when a loan defaults and increased when you record PLL expense, as follows.

[Original Allowance]-[Charge Offs]+[PLL]=[New Allowance]

When you make the transition from the incurred loss methodology to current expected credit losses (CECL), it is generally expected that your reserves will go up. This increase in reserves is recorded as a prior period adjustment to retained earnings, not through expense.

Further, let’s say you have a $100 million loan portfolio, a $1 million Incurred Loss Reserve (1%) on 12/31/2022 and a $1.5 million CECL reserve on 1/1/2023 (1.5%). Over the course of the year, some loans pay off, some loans charge off, and you originate new loans. In a hypothetical scenario where you have the same $100 million of loans next year (no growth) and the credit risk is the same, your end of year CECL reserve requirement would be the same as you beginning of year CECL requirement.

As a result, your PLL would be equal to your charge offs. This would be the case under both the incurred loss and the CECL methodologies.

To make a long story short, if your loan portfolio composition is not changing, your provision for loan loss expense, and overall profitability, will be the same under both the old and new methodology.

But all is not Equal

The problem with the example above is that loan portfolios are dynamic, not static. We all have growth targets and deploy strategies that cause our loan portfolios to change.

With a growing loan portfolio, your reserve under CECL will go up faster than under the incurred loss methodology, causing you to frontload provision for loan loss expense. When taking on more risky loans, the life of loan impact will be greater than it would have been under the incurred loss methodology, causing you to frontload provision for loan loss expense without being able to take the corresponding additional yield you’re likely incurring.

Frontloading this expense will cause Return on Assets (ROA) to fall in the short term. The issue though, isn’t that profitability is different, it’s that ROA on paper has changed. The issue is that the financial metric ROA is now limited in its usefulness. A metric that served financial institutions well when the matching principle was more strictly adhered to is now less reliable.

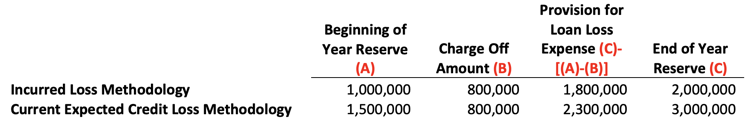

If we use the same example as previous, but assume the loan portfolio size doubles to $200 million, your end of year reserve would now (in a simple example) double, causing you to take more PLL expense under CECL.

As you can see, the end of year reserve grows more under CECL, causing you to record more provision expense in the short term and lower ROA. In practice, most in depth assessment of profitability focus on cash flows, not accounting returns. What I mean by that is, assuming a 5% interest rate on a $300,000 30-year loan, your monthly cash inflows are about $1,610. CECL doesn’t change that.

The opposite would be true during times of a shrinking loan portfolio. We’d actually take less provision expense with a shrinking loan portfolio under CECL, because we had recorded the provision expense upfront.

Bottom line: Profitable loans are still profitable. Financial Institutions performing well before CECL are still performing well after CECL.

Loan portfolio profitability has not changed, but the way we evaluate our profitability will have to in order to maximize the value that we’re bringing to our members.

The changes that will have to be made revolve around (a) focusing more on life of loan cash flows, or (b) modifying our traditional ROA metrics in order to adjust for mismatch in revenues and expenses created by CECL. One example might be adding back the portion of provision expense attributable to that year’s loan growth.

Don’t be caught by surprise when the changes to your financial statements hit. Now is the time to begin educating yourselves, other executives at your credit union and the board about how CECL will impact the way performance is assessed.